From Barter to Bitcoin

In recent years, Bitcoin has gotten a lot of media attention, mainly for its large price fluctuations. Especially in 2017, as the price of the digital currency was rising to new record heights, more and more people were jumping on the bandwagon, hoping to quickly get rich from this hype. This may have left the impression that Bitcoin is merely about price bubbles. However, in this article, I want to dive a little deeper into the economic value behind this digital currency by looking at a much broader concept: money. Text by: Ridho Hidayat

Direct and indirect exchange

What is money? At first glance, money seems to be a strange concept. Throughout the world people work 40 hours a week, primarily to see a number on their personal bank account go up. Intrinsically, you could say that this number is meaningless. Even in its physical form of currency, such as banknotes and coins, you could say that money is intrinsically quite useless. You cannot eat it, it does a poor job at keeping you warm, and you will have a hard time protecting yourself from wild animals with a €10 bill. So, what is money exactly, and why is it so important that we are willing to dedicate a large portion of our lives to obtaining it? To answer these questions, we need to look at the function and history of money.

Since the beginning of human history, exchanging value with one another has been a key aspect of any society. For example, one person makes bread, which provides food, while another person makes clothing, which provides warmth and protection. Both are needed for survival, and therefore it makes sense that these people may want to exchange these valuable goods in order to increase their likelihood to survive. The simplest way to do that is by direct exchange, also called barter. In the previous example, the bread is exchanged for the clothes. While barter has always existed throughout human history, it is highly impractical, especially in larger societies. The problem is that there is often a lack of coincidence of wants: what you want to acquire is produced by someone who does not want what you have for sale [1]. A person may not want to exchange his clothes for your bread.

The most logical way to overcome this problem is through indirect exchange.Indirect exchange means that you use a medium of exchange to get the goods that you want. Say you want to exchange your bread for clothes, but the person who has the clothes wants potatoes instead of bread. If you find someone else who wants to buy your bread for his potatoes, you can use the potatoes as a medium of exchange, so that you can buy the other person’s clothes. While any good can serve as a medium of exchange, as societies become larger, it quickly becomes impossible to keep track of everyone’s wishes. Therefore, it is much more efficient to use a single medium of exchange that everyone uses to trade their goods for. This is the primary function that defines money. It is not consumed, nor used in the production of other goods, but mainly used to exchange it for other goods. Thus, money can be defined as a good that is widely accepted as a medium of exchange.

Salability

In theory, any good could be used as money. So how does one specific good emerge on the market as money that is widely used by society? According to Carl Menger, there is one key property that leads to this: salability [4]. Salability is the ease with which a good can be sold on the market whenever its holder desires, with the least loss in its price. To measure the salability of a good, we can look at three different dimensions: salability across scale, space, and time.

- Scale: Can the good be easily divided into smaller units or grouped into larger units?

- Space: Can the good be easily transported or carried along?

- Time: Can the good hold its value into the future?

This last aspect, salability across time, is the most interesting, because it can be considered to be the second function of money: being a store of value. If money maintains its value over time, it means that it retains its purchasing power and therefore people can preserve their wealth.

If people would store their wealth in apples, they would quickly lose this wealth as the apples rot over time, and rotten apples are hardly worth anything. On the other hand, gold hardly deteriorates, as it does not naturally corrode over time. Therefore, physical integrity, being immune to deterioration, is a necessary condition for salability across time. However, it is not a sufficient condition. A good can still lose its value, even if it does not physically deteriorate.

A good can also devalue if its supply increases drastically, as it becomes relatively less scarce. Money whose supply can be largely increased is called easy money, as opposed to hard money, whose supply is hard to increase. For that reason, hard money is more likely to hold its value into the future.

There are two quantities related to the supply of a good that determine money’s hardness:

- Stock: the existing supply of the good, consisting of everything that has been produced, minus everything that has been consumed or destroyed.

- Flow: the extra production that will be made in the next time period.

The ratio between these two quantities, the stock-to-flow ratio, can be seen as a reliable indicator of the goods’ hardness. If a good has a low stock-to-flow ratio, it means that its supply can have a relatively large increase. If it has a high stock-to-flow ratio, its supply is more stable, and therefore the good is more likely to hold its value into the future and be more salable over time. Note that money’s hardness can change over time and with it its salability.

The problem with easy money, money with a low stock-to-flow ratio, is that it falls into what Saifedean Ammous calls the easy moneytrap: anything that is used as a store of value, will have its supply increased, and anything whose supply can be easily increased, will transfer the wealth from those who hold it as a store of value to those who can produce it at a low cost [1].

Let us take a look at a historical example. For centuries, aggry beads were used as money in western Africa [6], [7]. They were small in size, making them salable across space, they could be combined into chains, making them salable across scale, and most importantly, they were hard to produce in Africa as glassmaking was uncommon there, making them salable across time. When European explorers came to Africa, they quickly learned how valuable these beads were for the Africans. Since they were cheap to produce in Europe, they were made and shipped in large quantities, and traded for valuable resources including gold, slaves, ivory, and palm oil. Gradually, the beads lost their hardness, and with it, their purchasing power. However, during that process, the wealth of the Africans who held the beads as a store of value was being transferred to the Europeans who could produce them at a low cost.

The Gold Standard

For around 2500 years, gold, silver, and copper were the prime form of money in many civilizations around the globe. Among these metals, gold has always been the most salable across time due to its rarity and its resistance to decay, and therefore the most useful as a store of value. Even today, central banks still hold thousands of tons of gold in their reserves [9]. The reason for that is that gold’s hardness has a flawless track record; it beats the easy money trap. Even though people constantly increase the supply of gold for its function as a store of value, it cannot be increased significantly enough to bring the price down. Since the flow of gold is relatively low, due to its rarity, and its stock is relatively high, due to its indestructibility and the accumulation of thousands of years of mining, the stock-to-flow ratio is still very low.

From Ancient Greece to the early twentieth century, gold was mainly used to preserve wealth into the future. However, trading physical gold can be cumbersome. Transferring it can be troublesome, and more importantly, its high value makes gold less suitable for smaller transactions. While silver was used for smaller transactions, due to its lower value, the fluctuating exchange rate between gold and silver created additional trade and calculation problems.

More efficient trading became possible with the invention of new technologies, such as the electrical telegraph in 1837. This made communication easier, which resulted in the switch from a physical gold standard, to a monetary standard of paper. Bank papers were created, which were fully backed by gold or silver which was held in vaults. This was the modern gold standard. Everyone could use these bank papers at any time to redeem their gold or silver. People could simply store their gold in bank vaults and they could make payments of any size with these bank papers and checks, without having to physically transfer the gold. As long as the banks would not increase the supply of papers, gold could serve as the best monetary medium, being salable across scale, space, and time. However, this era, in which gold was chosen by the free market as the prime form of money, ended with the beginning of World War I.

Government money

At the start of the twentieth century, with the invention of modern central banks, governments brought their citizen’s gold under their control. The central banks held large gold reserves, while governments issued their own printed money, called fiat money, to the people. This government money became the standard medium of exchange, and citizens were often obliged to use this money, for instance, to pay taxes. It got its salability because it was under a gold standard, meaning that the paper money was fully backed by the gold reserves that were held by the central banks.

However, within a few weeks after the start of World War I, countries that were involved in the war suspended the gold standard. They started printing more money than they could back by their gold. The reason was simple: under the gold standard, governments could only spend what they owned, but by suspending the gold redeemability, they could also spend the wealth of their citizens. For as long as newly printed money was accepted by the population, governments would not run out of money to finance the war. Through inflation, and thus the devaluation of their money, citizens indirectly paid for the war. This allowed governments to wage war for longer than they otherwise could. By the end of the war, the supply of the German mark was six times larger than at the start [2]. This caused the German mark to devalue significantly, making their defeat inevitable. After the war, the value of the Reichsmark devalued a lot further as the German government printed more money to pay for the damages done to other countries. This eventually led to the hyperinflation of the Reichsmark.

While this may seem to be a unique historic event, hyperinflations have occurred more frequently and severely than one may think. It has occurred 56 times since the end of World War I according to Steve Hanke and Charles Bushnell, who define hyperinflation as an inflation rate of at least 50% over a period of a month [3]. The German hyperinflation only ranks 5th in the world hyperinflation rankings, with a peak of 29500% in October 1923. Zimbabwe takes the second place with a peak inflation of 79.6 billion percent in November 2008, and Hungary ranks first with a peak inflation rate of 41.9 quadrillion percent in July 1946. These are economic disasters that destroy all money savings of a society in a manner of months or even weeks, something which has not happened once in economies that used the gold or silver standard.

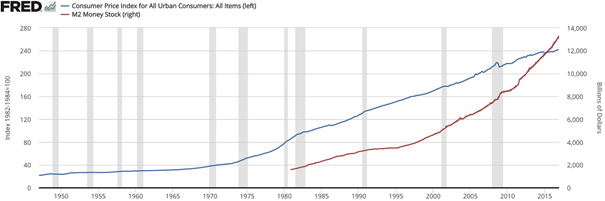

While hyperinflation only happens in extreme situations, money devaluation happens continuously now that economies no longer operate under the gold standard. This does not only apply to currencies of third world countries, but for instance to the dollar as well (albeit to a lesser extent), as can be seen in the graph below [8].

CPI-Urban (blue) vs M2 money supply (red); recessions in gray

There has been an average annual supply rate of about 6.0% since 1980, and an annual inflation rate averaging at about 3.5% since 1950. This means that the purchasing power of 1 dollar in 1950 is equivalent to the purchasing power of more than 11 dollars today. The reason is simple: the hardness of government money is only dependent on those in charge to not inflate its supply, in other words, political constraints. However, there are no natural, physical, or economic constraints to the supply rate. Thus, government money falls into the easy money trap: its supply is continuously increased, and the wealth of the holders is transferred to those who print the money or receive it first. We also see it happening right now, as governments are implementing multi-trillion dollar stimulus packages to face the current economic crisis. While it may help out some businesses, it significantly devalues the currencies in the process.

Since easy money does not hold its value into the future, this incentivizes people to spend it instead of saving it, thereby giving more value to the present than the future. This is called a high time preference, as opposed to a low time preference, in which people give more value to the future. The downside of a high time preference is that it focuses on immediate gratification. In the long run, it would be more beneficial to save resources, accumulate capital, and invest it to raise productivity. This would result in more income and higher living standards.

Bitcoin fixes this

Now, how does Bitcoin fit into all of this? How does this digital money work, and what can we say about its salability and hardness? To quote Yan Pritzker, Bitcoin can roughly be summarized by three different points [5] (p. 2):

- A digital asset (typically bitcoin with a lowercase b) whose supply is limited, known in advance, and unchangeable.

- A bunch of interconnected computers (the Bitcoin network), which anyone can join by running a piece of software. This network serves to issue bitcoins, track their ownership, and transfer them between participants without relying on any middlemen such as banks, payment companies, and government entities

- The Bitcoin client software, a piece of code that anyone can run on their computer to become a participant in the network. This software is open source, which means that anyone can see how it works, as well as contribute new features and bugs to it.

Let us further break down this summary. First of all, bitcoin is a digital asset, it is a currency that fully operates on the Internet. As such, it is a good that can be easily transferred across the globe, making it highly salable across space. Bitcoin’s supply is limited to 21 million coins, each of which is divisible into 100 million units that are now called satoshis*, for a total of 2.1 quadrillion satoshis. This makes the currency highly salable across scale, as you do not have to transfer entire bitcoins, but you can also transfer these much smaller satoshis. The big question that remains is: is Bitcoin salable across time? If it is, then Bitcoin is arguably a better form of money than both gold and fiat money, as gold is not very salable across scale (and less salable across space than bitcoin), and fiat money is not very salable across time.

The smallest divisible units are called satoshis, named after the person or group of people who developed bitcoin, known only by the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto

However, answering that question is much more difficult. And even though I will use the remainder of this article to argue that bitcoin is indeed salable across time, and thus a good store of value, it is advisable to read more about Bitcoin to be able to fully answer this question for yourself. That being said, why do many people believe that Bitcoin is salable across time?

The nature of digital objects is that they are not scarce. They can be reproduced endlessly, making it impossible to use them as a currency, because sending a digital object will duplicate it. That is why there is usually a third party involved, such as PayPal, which controls the digital currency, its supply, and the ownership of its coins. The problem is that a third party always adds a security risk, because you not only have to trust them that they do not increase the supply, but you also have an extra risk of theft or technical failure. However, Bitcoin is a game changer, because it does not require trust in third parties, nor can its supply be altered by any other party. The reason for that is that Bitcoin is built on a foundation of proof and verification, which removes the need for trust completely.

As stated before, Bitcoin is built on a network, and every transaction on the network has to be recorded by every member of the network so that one common ledger of balances and transactions is shared by the entire network. Whenever a sum is transferred from one member to another, all network members can verify that the sender has a sufficient balance, and nodes in the network compete to be the first to update the shared ledger with a new block of transactions roughly every ten minutes. Importantly, the node that commits a valid block of transactions receives a block reward consisting of newly created bitcoins added to the supply, along with the transaction fees paid by the people who are transacting. This process is called mining. In order to commit such a block to the ledger, a node must solve complicated mathematical problems that are hard to solve, but whose correct solution is easy to verify. Only with a correct solution can a block be committed and verified by all network members, which is called the proof-of-work (PoW) system. The larger the network, the more difficult it becomes to make invalid transactions, because a majority of the network needs to come to a consensus on what the state of reality is. Thus, with a larger network, you need to convince more nodes that a transaction is valid.

The quantity of bitcoins that are newly created is preprogrammed, even if more effort and energy is put into its proof-of-work system. This is done through a process called difficulty adjustment, which is the primary reason why bitcoin is hard money, and why the stock-to-flow ratio is low today and remains low in the future. As Bitcoin’s value rises, and people use it as a store of value, more effort is put into its production. However, this does not actually lead to an increase in the supply rate. Instead, the difficulty to commit valid transactions in the proof-of-work system increases, and therefore this extra effort only increases the security of the network, not the supply rate of Bitcoin. This makes Bitcoin resistant to the easy money trap, and actually, the hardest money ever created: growth in its value does not lead to an increase in its supply, but instead it only makes the network more secure and immune to attack. Therefore, Bitcoin remains to have a lower stock-to-flow ratio than the dollar or the euro, which is why it is likely that Bitcoin’s value (measured in fiat money) will increase over time, thus attracting more people to the network who use Bitcoin as a store of value.

The security in the network comes from the fact that there is an asymmetry between the cost of solving the proof-of-work that is required to commit a transaction to the ledger and the cost of verifying the validity of a transaction. Recording new transactions requires an increasing amount of electricity and processing power as the network grows larger, while the cost of verifying the validity of a transaction remains close to zero, regardless of the size of the network.

Bitcoin’s consensus rules

Lastly, the question arises: can a person or a group change Bitcoin? Can for instance its maximum supply be altered, the difficulty adjustment be removed, or the proof-of-work system be tampered with? What ensures that Bitcoin remains the hard money that it is right now?

In theory, this is possible, as the software is open source. However, in practice, it is highly unlikely. This stems from the fact that Bitcoin is both fully decentralized, and that everyone has a strong incentive to abide by consensus rules. Since it is fully decentralized, there is not a single entity that can change its rules. Furthermore, all participants have an incentive to abide by consensus rules:

- Programmers will only have their code adopted if other programmers accept their code, which is unlikely if it tampers with Bitcoin’s integrity;

- Miners have to abide by consensus rules to receive the block reward for the resources they spend on the proof-of-work system;

- Node operators are incentivized to abide by consensus rules because it ensures that they can make transactions on the network.

Every individual is dispensable to the network. Straying away from the status quo is likely to result in a waste of resources. As long as participants benefit from the Bitcoin network, and the benefit from the hard money that Bitcoin provides, it is likely that new participants will come up to replace individuals that strayed away. The consensus rules and specifications of Bitcoin can therefore be seen as sovereign. Bitcoin will only exist according to these rules and specifications for as long as it exists, and altering the rules and specifications becomes increasingly difficult as the network grows. For that reason, Bitcoin can be considered to be hard money, salable over time, and a good store of value.

Conclusion

Altogether, this article has hopefully given you some more insights into the history of money and the potential of Bitcoin. I have merely scratched the surface of Bitcoin, and I advise you to continue reading about the subject, for instance with Inventing Bitcoin from Yan Pritzker to understand the technical basics, or The Bitcoin Standard from Saifedean Ammous for the economic background, which I also used for this article. At last, if you would only remember one thing from this article, I hope it is the following: Bitcoin is not built to quickly make you rich. If anything, it is built to prevent you from slowly becoming poor.

References:

[1] – Ammous, S., “The Bitcoin Standard: The Decentralized Alternative to Central Banking”, Wiley (2018)

[2] DailyHistory.org, “What Were the Causes of Germany’s Hyperinflation of 1921-1923?, URL: https://dailyhistory.org/What_Were_the_Causes_of_Germany%27s_Hyperinflation_of_1921-1923%3F

[3] Hanke, Steve H., and Bushnell, C., “Venezuela Enters the Record Book”, Studies in Applied Economics (2016)

[4] – Menger, C., “On the Origins of Money”, The Economic Journal, Vol. 2, No. 6 (1892), pp. 239-255

[5] Pritzker, Y., “Inventing Bitcoin: The Technology Behind The First Truly Scarce and Decentralized Money Explained” (2019)

[6] – Quiggin, A. Hingston, “A Survey Of Primitive Money”, Routledge (1949)

[7] – Victoria and Albert Museum, “Trade Beads”, URL: http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/t/trade-beads/ (2016)

[8] Wikipedia.org, “Money supply”, URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Money_supply, data retrieved from Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

[9] World Gold Council, “World Official Gold Holdings as of May 2020”, URL: https://www.gold.org/download/file/7739/world_official_gold_holdings_as_of_May2020_ifs.xlsx (2020)